I made an awesome heritage day trip yesterday. My first encounter with Seahenge (Holme Timber Circle I) occurred in 1998. I was living at Thetford, and made daily visits to a local dig of a Pagan Saxon site there, by the NAU (Norfolk Archaeological Unit). On my last visit, the young digger remarked that he was being relocated to a remarkable timber circle rescue dig on the North Norfolk coast.

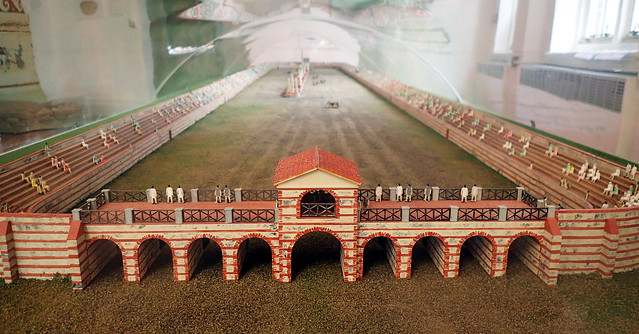

It was an eroded timber circle, with an inverted tree stump at the centre. It was dated through dendrochronology to be 4,060 years old (2049 BC) felled and erected during the Early Bronze Age. There were concerns that the site could soon be lost to sea erosion. An attempt was launched by the NAU in collaboration with the TV show Time Team, to remove the timbers from the beach for conservation. There was significant protest by both local groups, and by neo-pagans, that felt that the timbers should be left on the beach.

The removal continued despite the protests. It has been postulated that it may have been used as a small shrine, or perhaps as a burial chamber - with the corpse placed on top of the inverted tree stump "altar".

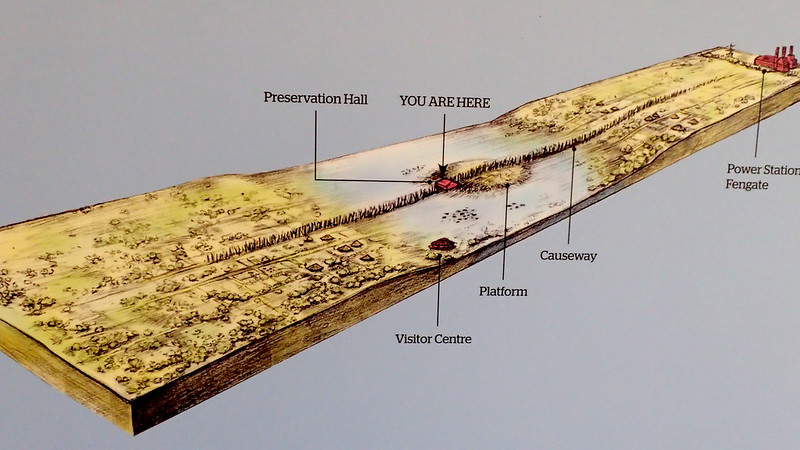

I next saw the timbers a few years later, under preservation process at the Flag Fen archaeological museum near to Peterborough:

The tanks at Flag Fen were under canvas, and you could literally touch the timbers in the water tanks. Since preservation was completed, most of the timbers, and the tree stump "alter", have been on display in Norfolk, at the Kings Lynn Museum. I've visited it several times over the years, but I had never been to the original site. Until yesterday!

I parked the car back near to the White Horse pub in the village. I wanted to take a short pilgrimage of a few miles to the spot that I had identified from grid references online. It also follows where the Peddars Way joins the North Norfolk Coastal Path. Two long distance trails that I completed with my dog years ago.

Been there, done them, got the T shirt.

The path follows behind the sea dunes and a stretch of freshwater marsh - that is most likely, similar to the environment that the timber circles were built in. Sea erosion over the past 4,000 years has been driving the sealine and dunes back. The dunes must have gradually crossed over the timber circles as it slowly retreated, leaving the archaeology on the beach surrounded by the eroding features of ancient fresh water marshes.

I had pre-programmed my trusty handheld GPS unit to track down the find spots.

I can't tell you how much I loved retracing my old steps along this section of the North Norfolk Coastal Path. It's beautiful:

When I started to near to the point, and to the archaeological site, I safely traversed a foot path down to the beach. An awesome, beautiful day:

I followed the GPS to the find spot here. During the dig, it was alongside a patch of ancient marsh mud. It's all gone. Just bleached sands now. A few years after removing Seahenge (Holme I), a second timber circle (Holme II) and altar was spotted close by. It was a larger circle, with planks rather than posts, and signs of a timber causeway near by. Following the experience of the public opposition to removing Holme I, it was decided this time, to leave this other timber circle in-situ. Today, it appears to be gone. Eroded away by storms and tides. Clearly, the archaeologists and conservators were perfectly correct to have removed the smaller circle for preservation. The above photo looks across where the two circles were. A metal rod presumably left to mark the spot of Holme I:

More modern timbers can be found closer to the eroding marsh mud:

Some timbers on the site have also been identified as being much older tree stumps from the old marsh.

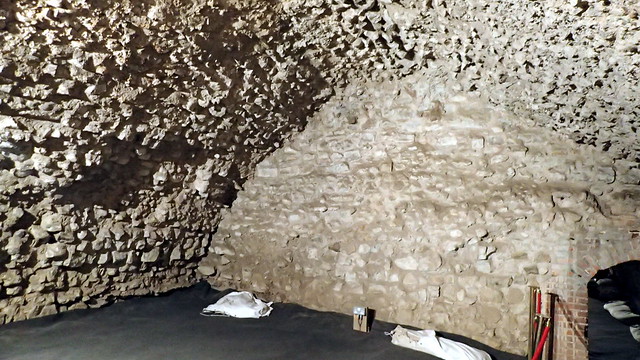

Then it was off the Kings Lynn Museum, in order to revisit the timbers of Seahenge (Holme I) circle:

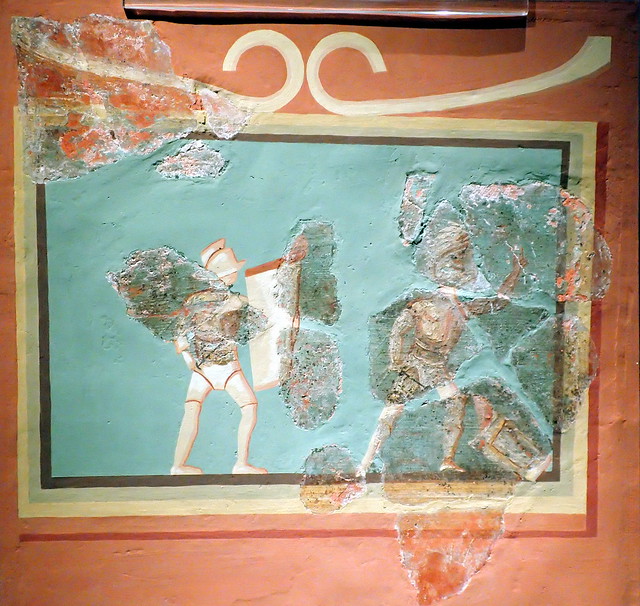

Below, a reconstruction of an Early Bronze Age man (carrying a flat bronze axe), based on the dress of contemporary bog bodies found in Denmark:

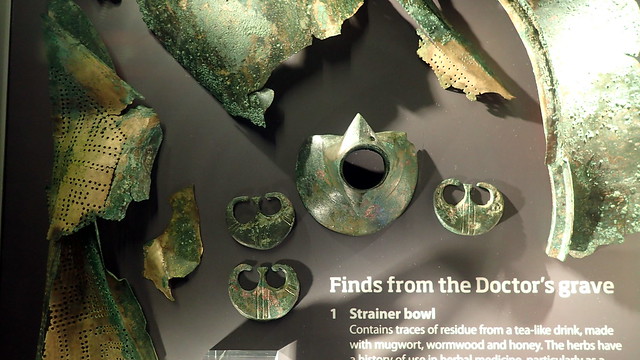

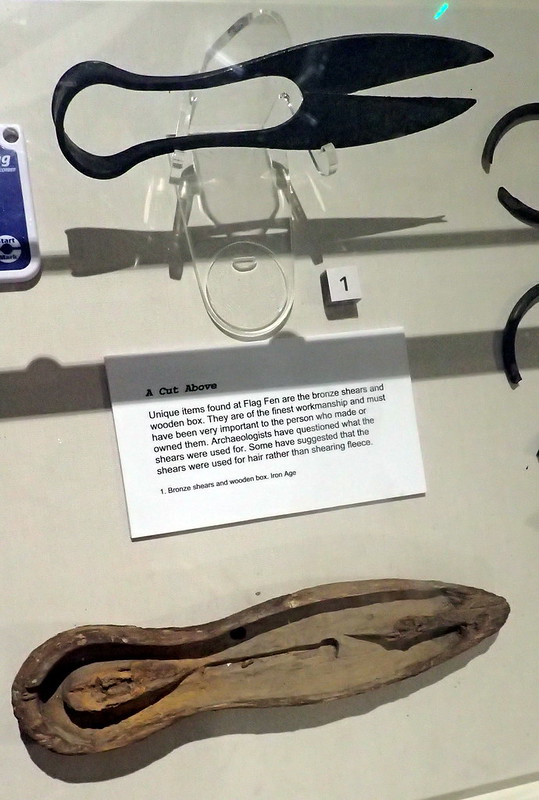

Finally, a display case with other Bronze Age finds from the area:

Population Genetics Discussion.

Only within the past few weeks, a major new study of ancient European DNA has suggested that the earlier Neolithic peoples of the British Isles were largely replaced (or even perhaps displaced) by a new people carrying an artifact assemblage that we call the Bell Beaker Culture, most likely arriving first in Southeast Britain, from what is now the area of the Netherlands. They would arrived in the British Isles circa 4,200 years ago. This is just previous to the Holme Timber Circles. The conclusion would be that most likely, the timber circles on the North Norfolk Coast were the burial practices of this new Beaker population. However... the story remains to be detailed, or even perhaps rewritten with future study.