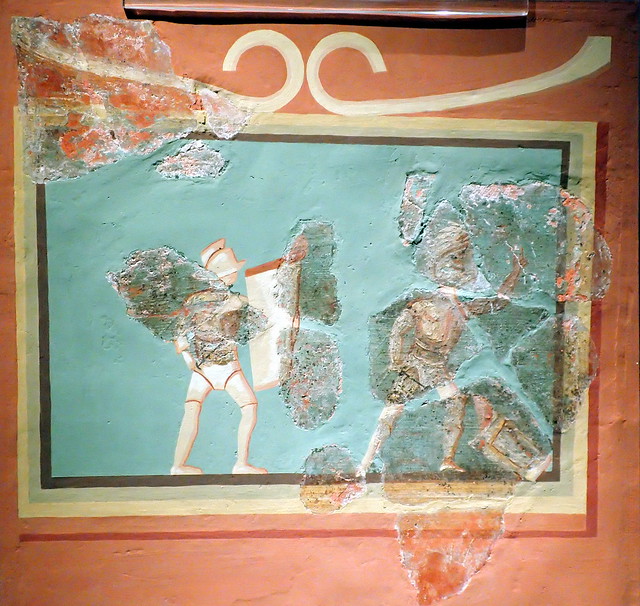

I took the above photo of a Roman tombstone at Colchester. It's the image of a Roman cavalry officer, ruling over a defeated Briton. It had apparently been damaged during the following Boadiccan Rebellion. No doubt the Iceni-led rebels against Roman authority would have found this image a tad humiliating. The point that I want to make here though, is that the cavalry soldier that this tombstone commemorates, may have been Roman, may have died in South-East Britain, but actually hailed from what is now Bulgaria!

The archaeological and historical evidence suggests that as a foreigner in Roman Britain, he was far from alone. There are a number of similar stories, that suggest that Roman Britain was visited by many other people from across the empire - not only people from what is now Italy and Bulgaria, but also from what is now the Netherlands, France, Greece, Syria, Lebanon, Germany, Spain, Tunisia, Algeria and Iraq. Visitors appear to have included not just military, but merchants, specialists, politicians - they all occasionally stare out at us from the archaeology and histories of Roman Britain.

We know that they were here.

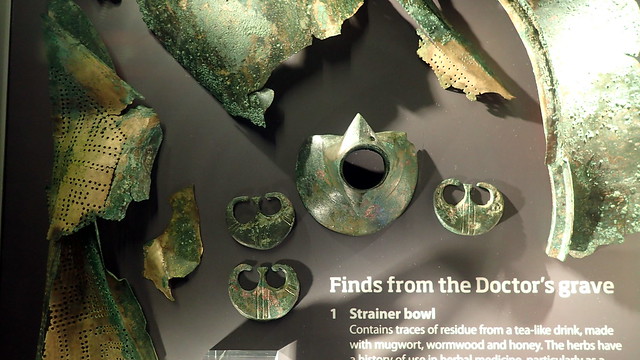

Previous anthropological investigations at Trentholme Drive, in Roman York identified an unusual amount of cranial variation amongst the inhabitants, with some individuals suggested as having originated from the Middle East or North Africa. The current study investigates the validity of this assessment using modern anthropological methods to assess cranial variation in two groups: The Railway and Trentholme Drive. Strontium and oxygen isotope evidence derived from the dentition of 43 of these individuals was combined with the craniometric data to provide information on possible levels of migration and the range of homelands that may be represented. The results of the craniometric analysis indicated that the majority of the York population had European origins, but that 11% of the Trentholme Drive and 12% of The Railway study samples were likely of African decent. Oxygen analysis identified four incomers, three from areas warmer than the UK and one from a cooler or more continental climate. Although based on a relatively small sample of the overall population at York, this multidisciplinary approach made it possible to identify incomers, both men and women, from across the Empire. Evidence for possible second generation migrants was also suggested. The results confirm the presence of a heterogeneous population resident in York and highlight the diversity, rather than the uniformity, of the population in Roman Britain.

Leach, Lewis, Chenery etal 2009

I could have alternatively used more historical evidence of individuals - the General from Tunisia, the Syrian in Northern Britain, with a Southern British born wife, the York woman that appears to have had mixed African ancestry, etc, the recurrent Greek names, the Syrians, Algerians and Iraqis that patrolled Hadrians Wall. As Charlotte Higgens stated in Under Another Sky, Journeys in Roman Britain 2013:

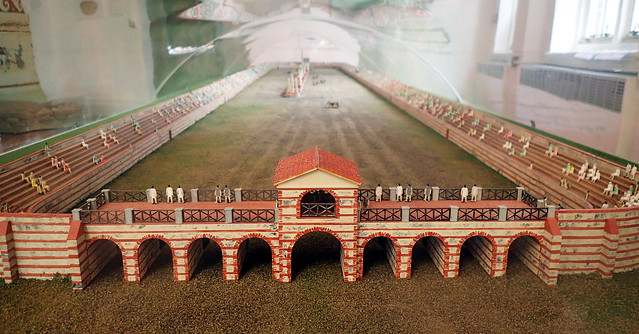

"In Roman Britain, you do not have to look far to find traces of people sprung from every corner of the empire. Because of the Roman's insatiable desire to memoralise their lives and deaths, they left their mark. Some fell in love, had children, stayed. Many no doubt to, were brief visitors, posted to Britannia and then off to the next job, in Tunisia, perhaps, or Hungary, or Spain. In the Yorkshire Museum is an inscription made by a man called Nicomedes, an imperial freedman and probably Greek, to go by the name. He placed an altar to the tutelary spirit of the provenance - 'Britanniae sanctae', sacred Britannia. Also in York, a man called Demetrius erected two inscriptions in his native Greek - one to Oceanus and Tethys, the old Titan spirits of the sea; the other to the gods that presided over the governer's headquarters. The Roman empire was multicultural in the sense that it absorbed people of multiple ethnicities, geographical origins and religions. But Roman-ness - becoming Roman, living as a Roman - also involved particular and distinctive habits, architecture, food, ways of thinking, language, things that Romans held in common whether they were living in York or in Gaza.".

South east Britain was a part of the Roman empire for no less than 370 years, and was strongly influenced by it both before and after that membership. That represents quite a few generations, maybe around 12 to 18 generations. So in AD 410, as locals in Britannia fretted about their Brexit, Germanic immigration, and were petitioning Rome to send the troops back, some of their pretty distant ancestors, had witnessed the arrival of Rome with the Claudian Invasion. That's a long time for contact and admixture to drip feed.

Did this long membership of the empire leave a genetic signature in Britain? The current consensus is no! We have not yet found anything in the British admixture, that can be ascribed to Roman Britain. Not on an autosomal DNA level. The given explanation is that the Romano-British admixture experience was so cosmopolitan, and diverse, that no one contributing population managed to leave a lasting signature. Each case was apt to be washed away by the phenomena of genetic recombination. It hasn't left a background admix in modern South-East British populations that has yet been detected and recognised.

However, enthusiasts that test their DNA haplogroups do often find results that are not easily explained by conventional British population history. Odd haplogroups turn up. My own Y-DNA, L-SK1414, with a Western Asian origin, is just one example. Perhaps some of these rogue haplogroups in Britain, are a smoking gun of Roman Imperial experience.

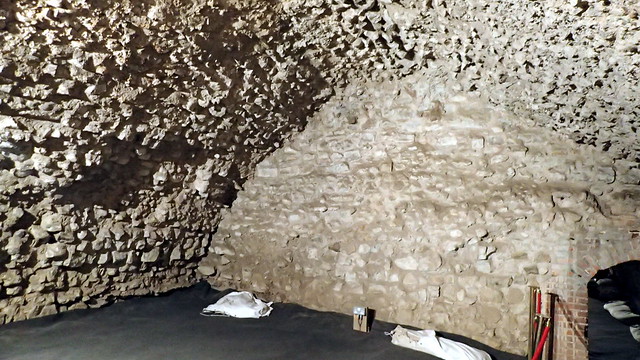

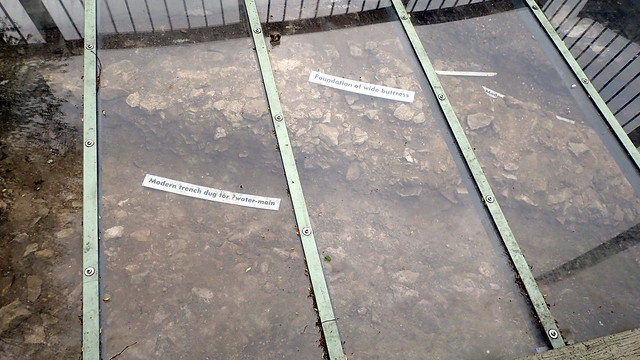

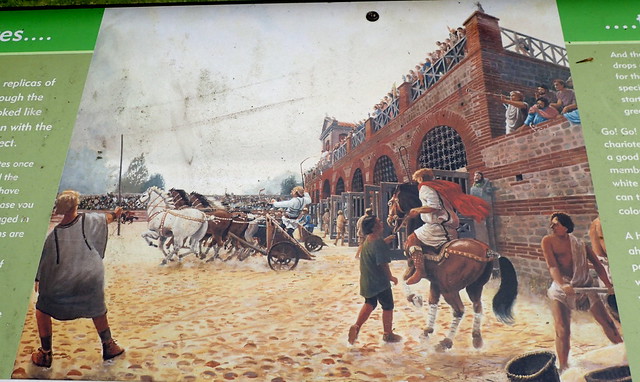

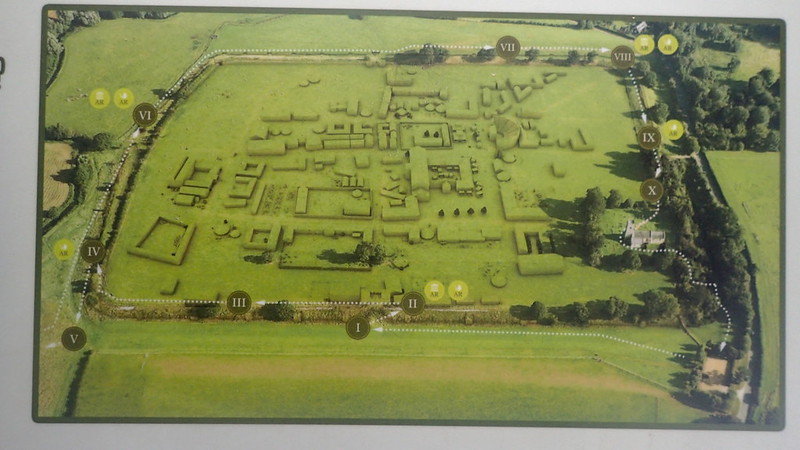

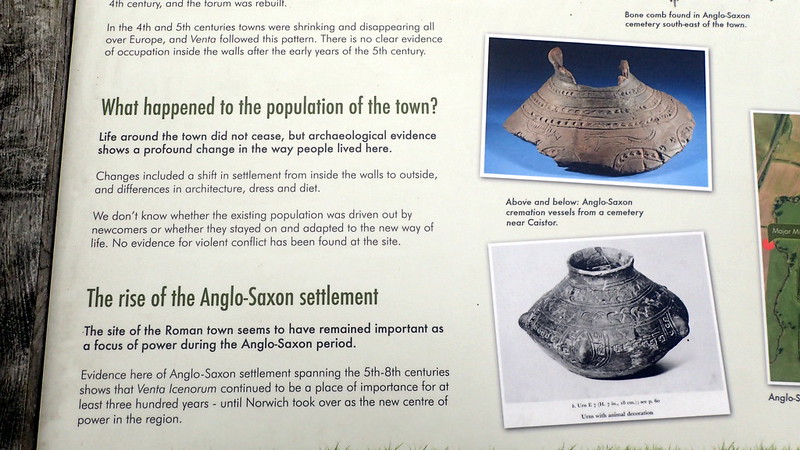

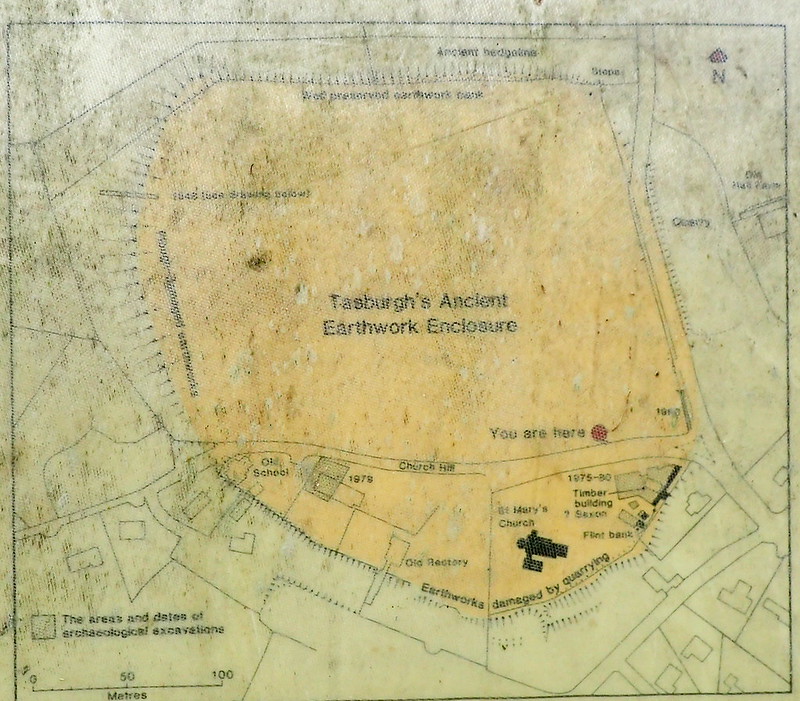

The site of Venta Icenorum here in Norfolk.